- Home

- Leah DeCesare

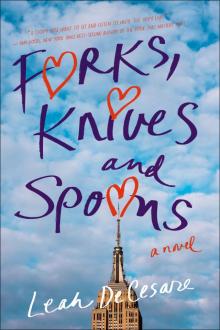

Forks, Knives, and Spoons Page 8

Forks, Knives, and Spoons Read online

Page 8

“Do you have a list?” Jenny asked abruptly.

“A list?”

“Yeah, you know, a list of the things you want in a guy.”

“Yeah, I have a list.” Her eyebrows pinched together as she smiled, somehow both amazed and unsurprised that they had this in common.

“What’s on it?” Jenny asked.

“Well, there’s the list of things I really want, like he has to be responsible and kind, not afraid to show his emotions, and he has to support me in my journalism career and have a job of his own, of course. I want a guy who will be a true partner, who completely gets me.” Amy thought of Andrew and smiled. “Maybe it’s unrealistic to think a guy could completely understand me, but I want to feel like he does, or at least tries.”

Amy rattled off some of the traits memorized from years of writing and editing her list. She pictured the pale green sheet of copy paper, folded and folded upon itself into a small square that she kept tucked in her Treasure Box. For her sixth birthday, her dad had built the box and painted it yellow with her name on top; she had instantly dubbed it her Treasure Box.

“Then there’s the list of things I don’t want, things that are sort of deal-breakers.”

“Like what?”

Without hesitation, Amy answered using the language that all the Brewster 8 girls conversed in: “A slotted spoon or a fork. Someone who doesn’t care about his grades or his job, or someone who’s mean to people. If he can’t be nice to the waiter or his own mother, someday he’s not going to be nice to me. And most important is trust. If I can’t trust him, forget it!”

Jenny whiplashed in a new direction. “Why is it just you and your dad?”

Amy paused. Her friends in Newtown knew and she had rarely had to explain, but since starting college, she’d had to share the story more often. She gave Jenny the quick version.

“I never knew my mom. They were older parents, waiting while my mom fought cancer. She finally was given the all clear and got pregnant. In her sixth month, they learned the cancer was back. They did what they could, but she died when I was only seven weeks old. It’s been my dad all along; we’re really close. I guess you can understand that since it’s just you and your mom.”

Jenny shrugged. “Not really. My mom and I fight more than we get along. We love each other, of course, but honestly, I’m not that close to her. She works a lot and goes out with different guys who aren’t really interested in having me around.”

There was so much about Jenny she didn’t know, Amy thought, despite how—with the intensity of time together and the immersion in life’s details—it seemed that at college, floor-mates got to know each other more quickly and more personally than in high school relationships. Quirks were in full view—there was no hiding them while living together—and it wasn’t just between roommates that secrets were revealed and personal preferences displayed. Living together meant sharing idiosyncrasies with the whole floor.

They lived with women who could recognize one another by the feet glimpsed beneath toilet stalls, easily matching flip-flops to their owners. They brushed teeth side by side, witnessing a variety of approaches, from the closed-mouth brusher to the talking-while-brushing style. There were girls who turned off the water as they brushed and girls who left it running until the sink filled; brushers whose spitty toothpaste bubbles dribbled down their wrists and brushers who meticulously spit into the drain and rinsed the sink. Just the simple, everyday act of brushing one’s teeth divulged a world of differences, but it didn’t let you see into another’s heart and home life.

THOMAS YORK WAS WAITING at the station to pick up the girls. His once-brown hair was heavily peppered with white and swept neatly into place. He was dressed casually in jeans and a gray sweater with a blue collar poking out. He kissed Amy’s cheek as he took the biggest bag from each of the girls. Once they were loaded into the car he said, “Come here, kiddo,” and pulled Amy into a full embrace. “I’ve missed you!”

Amy wrapped her arms around him and relaxed into being with her dad. “I missed you, too, Dad.” The words vibrated into his chest as she smelled the familiar scent of him, leather and wood. The scent of home.

To her side, Amy noticed Jenny stuck in place, watching the scene as though watching a movie. Her face was frozen but her eyes followed along.

AFTER CLEANING UP from a light supper, the girls helped Amy’s Aunt Joanie in the kitchen with the final Thanksgiving meal preparations. Aunt Joanie and Uncle Arthur always came down from Vermont and helped Joanie’s brother hold up the Thanksgiving tradition of hosting their family. Amy felt soothed by mixing the pumpkin filling ingredients and pouring them into the hand-sculpted piecrusts. While Amy baked, Aunt Joanie put Jenny in charge of laying out the silver and crystal at the table set for eleven, wedding gifts that Amy’s mother had loved and that her father insisted on each year. It took all the leaves of the dining room table to accommodate everyone.

“Wow, you guys really go all out!” Jenny admired as she fingered the cloth napkins and placed the salad fork outside of the dinner fork. Giggling, she popped her head into the kitchen. “Hey, Amy, is there a silver fork in your silverware system yet? Maybe he’s a really cocky guy who is also a total rich snob. Maybe a silver fork is born with a silver spoon in his mouth.”

“Someone who treats a woman like his possession.”

“Oh! And maybe a silver steak knife is the perfect guy who is also filthy rich, someone like John F. Kennedy Jr., Rob Lowe, or Jon Bon Jovi,” Jenny added.

“What are you girls talking about?” Aunt Joanie asked as the phone rang.

Chuckles still bubbled from her lungs as Amy grabbed the white kitchen phone from its wall cradle. “Hello?”

“Hi, Aim, it’s me.” Andrew’s voice caressed her across the distance. “I miss you.”

She stretched the long curly phone cord from the wall, across the kitchen, around the corner, and into the bathroom. She sat on the edge of the toilet cover, threading her finger through the loops of the cord. He called, she thought, on our first day apart.

“Miss you, too. I’m happy you called.” Amy dropped her voice to a hush, feeling a special intimacy in the privacy of their call. She leaned back against the toilet tank and twirled the phone cord like a jump rope, letting it slap the tile floor with every turn.

“How’s it going with Jenny? You hanging in there?”

“Actually, it’s going great, she’s nice,” Amy replied as a lilting voice cooed in the background on Andrew’s side of the line before a man’s voice cut in.

“Hello? Hello? Who’s there?”

“I’m on the phone, Dad,” Amy answered into the phone.

“Already? Okay, but be snappy, I’ve got to make a call.”

“Dad, please! Hang up!” She blushed alone in the dim bathroom as her father replaced the receiver elsewhere in the house.

“Happens here, too,” Andrew assured her. “My mom and sisters are constantly picking up the phone when I’m on it.”

“Come on, Andrew, it’s our turn, everyone’s waiting. Who are you talking to?” Amy heard a girl flirt clearly, as if she were speaking directly into the phone, which meant that her mouth was very near his. When she could no longer make out the muffled words, Amy knew Andrew had pressed his hand over the receiver. The tip of Amy’s finger purpled while she waited. She unwound the coil, releasing her finger then tangled another one into the white rubbery ringlets. She resisted acting the jealous girlfriend though her stomach felt the undeniable wobble.

“Sorry. I’m back,” he said.

“Guess you’ve got to go.” The words spilled out involuntarily and she hoped they didn’t sound demanding.

“Yeah, I guess I should. Some high school buddies are over. Bree and the girls organized a game of Trivial Pursuit,” Andrew explained. “Next they’re planning Truth or Dare.”

Amy pushed out an insincere laugh, not knowing if he was serious. Who played Truth or Dare at their age? She wondered exactly how Andrew

felt about her, wondered exactly where she stood. Then she dismissed the thought, he had called because he missed her, hadn’t he? And he was honest with her about Bree being there, he wasn’t hiding it, she reasoned. So why did she still feel apprehensive knowing he was with his ex-girlfriend?

“THANK YOU FOR A delicious meal, Aunt Joanie,” Jenny said, scraping the last plate and stacking it into the sink. “And what a great family you have.”

Before Amy’s aunt could answer, her dad walked into the kitchen. “Come on, girls, let’s go for a drive,” he said. It was a statement more than a suggestion. Joanie smiled to herself, accustomed to her younger brother’s timing, and plunged her yellow-gloved hands into the soapy water.

Jenny looked at Amy as she tugged her arm into her coat. “Where are we going?”

Amy shrugged. “Nowhere, really.”

From the time Amy was a young girl, Tom York would take her out for drives around their hometown. When he wanted to talk to her, he’d announce, “Let’s go for a drive,” and head to the garage. At some point, she understood it was easier to approach certain topics without having to make eye contact. These drives stirred in her a mixture of excitement and dread, as it was cherished time with her dad tangled with the wondering of whether something was wrong. As he weaved the car through the wooded roads, he’d open his discussion, Amy in the front seat beside him.

“So, Dave’s been hanging out at the house a lot lately,” he’d begin, shifting in his seat. “You two are getting quite close.”

“Not in that way, Dad, he’s just a friend. He’s like hanging out with a brother.”

“Does Dave feel that way?”

“Really, Dad, you’re not even close on this one. We’re friends, of course Dave knows we’re just friends.”

In a cryptic, halting speech, her dad would try to clue her in to how guys think, to how they act when they like a girl. He tried to enlighten her on what Dave was really feeling.

“We’re just friends, Dad,” she’d insist, dismissing his analysis of the situation. She denied his words aloud and ignored the nudge in her gut, thinking of the moments when friendships had blurred into something more.

Driving a little longer before winding back home, the conversation would shift to easier subjects like school and sports. That was the general formula for one of Thomas York’s drives with his daughter and, now, with Jenny.

“Sit in the front, Jenny,” her dad directed, and Amy slid to the middle of the backseat where she could lean forward between them.

Sticking his favorite album into the cassette player, they drove through the back roads with only the sound of Billy Joel singing before Tom York spoke. His eyes focused on the road, and his left arm rested along the window. “So, Jenny, was this your first New England Thanksgiving?”

Amy breathed relief: he was starting slowly. Sometimes he just dove right in to whatever he was thinking. Then in the next instant, there it was.

“You live alone with your mom?”

Oh, no, Amy thought, where is he going with this? She worried that Jenny would feel uncomfortable and she opened her mouth to buffer the situation for her, but Jenny was already answering, her voice sounding at ease.

“Yes, it’s just the two of us. Sometimes we spend holidays with my mom’s sister, who lives a couple of hours away, or sometimes with a guy she’s seeing, but it’s quiet around our house. My mom’s a nurse and has long shifts, so sometimes it’s just me at home.”

Jenny was sharing more with Amy’s dad than she had with Amy in months at school. Amy slid back into the darkness and watched the streetlights flash squares of gold on the seat beside her.

“Where’s your father?”

Amy’s head flew up at the question. Jenny had never mentioned her father except for the story about the tea set he had given her as a child. Amy assumed her parents had divorced, but then seeing how upset she was over the tea set, she thought maybe he had passed away. Amy held her breath and tilted her head, aiming her ear toward the front seat.

Jenny inhaled audibly. “He left.”

Amy’s father kept his eyes forward. He gave a single nod and Jenny continued.

“He left when I was six. I was playing outside on the front steps, with a purple tea set—” Her voice caught but she went on. “He kissed the top of my head and, like he always did, said, ‘Good-bye, Jenny-Doe’—that was his nickname for me—and he drove away. I never saw him again.”

Amy’s heart clenched, her hand floated unconsciously to her chest. How incredibly awful, she thought, how painful and sad. Instantly, she saw Jenny differently. Her promiscuity and flirtations, her forced perkiness and painted-on confidence, were changed with this new perspective on her past.

Amy’s dad cleared his throat. “I’m sorry, Jenny, that must be very hard for you. There’s something I want you to remember.” He paused, choosing his words. “Remember to value who you are no matter what. Believe you are worth being loved and don’t ever settle.”

Jenny’s head dropped forward and she swiped a finger across her eyelid. Her whole life, Amy had heard the words her dad told Jenny. She had internalized the message, having received it time after time. Her father helped shape how Amy saw herself. He had worked to build her self-confidence in moments accumulated and cemented through years of repetition, and it shocked her to realize that Jenny may never have been told by her own father that she was important, that she mattered. Is it possible that she doesn’t know that she deserves love and respect?

Amy felt a surge of compassion toward Jenny and increased admiration for her own father. How had he known that Jenny needed one of his drives? How did he know what to say to her, how to get her to share?

Then her dad spoke again. “You know, life will bring you ups and downs, good times and bad ones, and you need to love yourself to be able to handle them.” He looked to Jenny. “Never forget that. You have to love and value yourself.” As they turned to head back home, he turned up the volume on “Piano Man” and asked, “So, what are your plans for tomorrow, girls?”

VERONICA’S PARENTS WERE HOSTING their annual Thanksgiving eve Warren Foundation fundraiser her first night home. She had just enough time to change and pin up her hair before she was expected to wade through the crowd of her parents’ friends, smiling and repeating the answers to “How is school?” “What’s your major?” “Happy to be home?” “How’s Eric?”

She watched in the distance as Susan Warren floated among her guests, grinning effusively, and as her father laughed grandly, slapping shoulders in a circle of men. All she wanted was to curl up in her pajamas, sit around the kitchen table, and tell her parents about school, but she smiled and moved on to the next group.

“I’m glad I got to see you, Mrs. Everett. Say hi to Bitsy for me.”

“Oh, she goes by Elizabeth now, dear.”

Veronica nodded and turned toward the crowded living room, thinking she could say a few final hellos and then slip away upstairs.

“Veronica.”

She recognized the voice and found herself facing Mr. Eric Sheridan Sr., his familiar face turned serious. His eyes drilled into her and she felt like she was looking into Eric’s.

“So you went and broke our boy’s heart,” he began.

At first, Veronica thought he was joking, but his gaze said he wasn’t. She opened her mouth to speak but shock stole her words.

“Mrs. Sheridan and I were very disappointed to hear that you won’t take any of his calls, just cut him off,” he continued, filling the space where Veronica should have spoken.

“I—he—but—it’s that—” Veronica stammered, screaming at herself inside to form a sentence, to respond. “We both decided it wasn’t working out.” Her Newport upbringing propelled her to weave the little lie to protect Eric, to protect his parents from the truth, even as he clearly laid the blame on her. That fib battled inside her. The truth rose in her throat swimming for air. She swallowed it down.

“You know, Veronica, men have a lo

t of responsibility. Eric is at Brown, after all. In the end, it’s the woman’s job to make it work out,” he accused.

Her manners tempered her words, and spinning some sugar from the bitterness, she said, “Nice to see you, Mr. Sheridan. Happy Thanksgiving.” Then she headed toward the kitchen and the back staircase to her escape.

Comfy in pj’s, she called to tell Amy.

“What an antique fork,” Amy said, concocting a UCS label for Mr. Sheridan. “That gives us a lot to consider. Does that mean forks don’t grow out of it? Once a fork, always a fork? I wonder, can an antique fork change his tines?”

Veronica caught herself smiling, grateful for Amy’s perpetual cheer.

VERONICA PADDED INTO THE kitchen to the smell of turkey roasting and serving dishes laid out on the counters, labeled neatly with what would soon fill each one.

“Morning, sweetie.”

Her mother was already showered, made up, and dressed with an apron over her slim wool skirt and fitted sweater in a matching shade of Wedgwood blue. She had ordered most of the meal from her favorite caterer and would have help preparing and serving the banquet, but she insisted on the tradition of making homemade stuffed mushrooms, her grandmother’s recipe.

“How are you already up and ready, Mom? What time did the party end last night?” Veronica covered a yawn with the back of her hand as she poured coffee with the other.

“Oh, I don’t sleep much anymore, you know, not since, well, since, you know,” her mother said, lowering her voice as if avoiding a forbidden word, and then she shook her head, shooing the thought that was always there, and continued with energy. “So, I’ve arranged a lovely date for you for tomorrow night.”

“What? No!” Veronica moaned. “Mom. Why?”

“Now don’t argue, he’s the son of Daddy’s accountant. I’ve heard he’s quite a catch.” Her mother rubbed the dirt off a mushroom cap. “His name is Ian Curtis and he’ll be here at seven tomorrow night.”

“Mom, you’ve ‘heard’? Heard what? From who? Ugh! I can handle finding my own dates. In fact, I’ve been seeing a great guy named Scott, he’s even a Phi Psi like Dad,” Veronica protested, though she knew it was no use.

Forks, Knives, and Spoons

Forks, Knives, and Spoons